The East-Indian Voyage of Wouter Schouten

By Michael Breet, with Marijke Barend – van Haeften;

Walburg Pers, Zutphen 2003

Translated by Carel Tenhaeff, 2015

About Wouter Schouten

Wouter Schouten of Haarlem, the Netherlands, was a surgeon working for the Dutch East India Company in the 17th century. He joined service because he loved traveling, and he described his observations elaborately. His journals were published in Amsterdam. He made lovely drawings as well, which where etched and printed in his journals.

The following text is part of “Book 3, chapter 2, pp. 325-331: Pipeli”

The year 1662, thanks to the mercy and benevolence of God, had come to an end, and once more all of us felt obliged to praise and thank the Most Supreme One for His help and protection. In the early morning of the 1st of January, 1663, we fired the heavy artillery a couple of times, and wished each other hail and blessings for the new year. Throughout the day we left our flags and streamers blowing in the wind (2)

We now began to take in a load of saltpetre, but were troubled in this by the sudden emergence of an enormous storm, which lasted for two days and put us in an awkward predicament. On the 4th of January, at first there was a dark sky with drizzling rain and a stiff breeze from the North-East, which turned into a heavy storm by the evening. By this we were broken adrift from our anchor, but immediately we dropped two other heavy anchors, and brought down the booms and yards. Since we had to do with a land wind, the water surface was reasonably smooth so far, but we feared that, if the wind would rotate, we might not prevent a shipwreck. Due to the Northern storm it was so cold that one was afraid to put one’s nose on airs. The crew chattered their teeth and blew their hands as if it was a Dutch winter. The oil in themedicine boxes was frozen stiff due to the cold; the woollen togs and knickerbockers came in handy here, but there were so few of those, that the sailor who appeared with an old patched-together Dutch frock or skirt on the landing with his colleagues, felt happy as a king.

As for us, we had provided ourselves timely with handsome quilted Bengalese coats, lined with soft and pure kapok, and manufactured by the Moors in a skilful manner out of all sorts of beautiful fabrics. Our old assistant merchant, Cornelis van der Manden, who had already been sickly before, collapsed because of the unusual cold, and came to expire shortly afterwards. According to sailing usage we therefore hang out the flag halfway on the boom of the upper deck, fired three gun shots, and buried him in the Company Garden of Pipely together. Here, there are handsome tombs of both Moors and Dutchmen.

After the storm had spent itself, a number of ships, which had joined us coming from the Ganges, left for various destinations: the Nieuwenhoven, ‘t Raadhuis and Peperbaal to Batavia (3); Brouwershaven, Ter Veer and Pegu for Persia; Pipely and another Morish little ship for Masulipatnam and other places at the Coromandel.

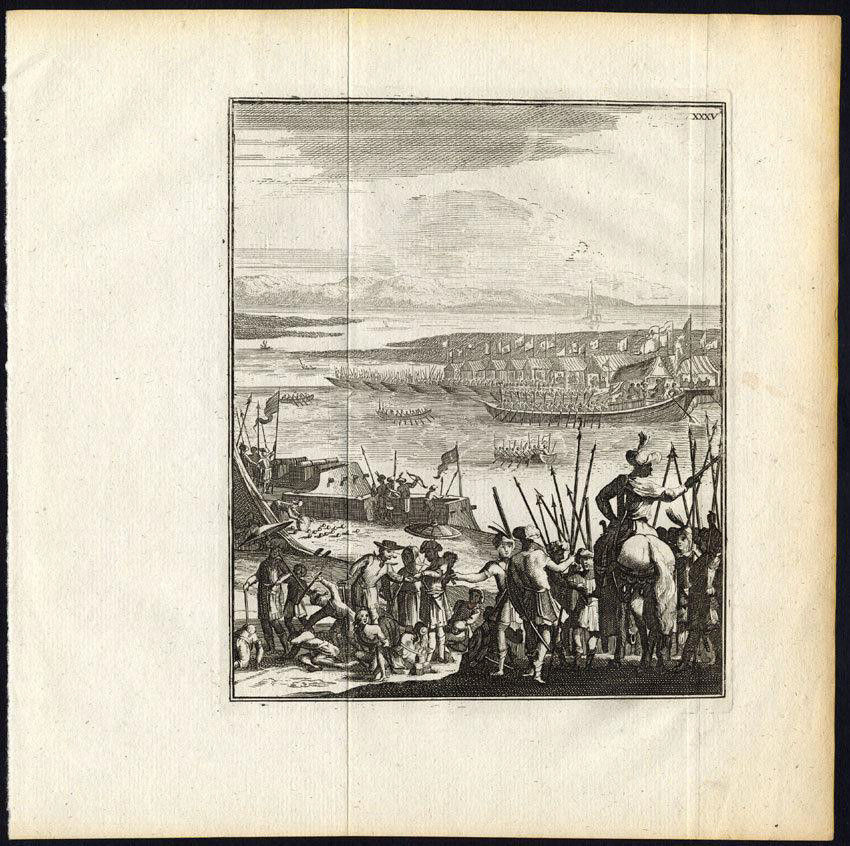

In the early morning of January 22nd, ten jeliasses or plundering galleys from the kingdom of Arakan descended from the Ganges onto the river of Pipeli. This caused unrest, because they were stuffed with brave, armoured people, and had a large crowd of Bengalese slaves and men, women and children on board. They had captured these in course of the journey from Arakan, not at sea but while sailing along the Ganges in the inner waters, with violence, after hamlets and farms had been plundered and set on fire. Also they were carrying a large booty of silver, gold and gems, of which they had robbed these people, and which they were now, here and elsewhere, trying to sell off. They tried to sell their captives as slaves, and for this reason were sailing further down the river of Pipeli in an orderly manner. On the way they ran into us, and asked if we did not feel like buying beautiful Bengalese male and female slaves, and if so, that we could safely come and see them. After that they continued their journey, and halted at the Thieves’ Island, which is situated halfway Pipeli. Dismay prevailed amongst the Bengalese about the advent of these enemies, who, at this time of the year, are coming from Arakan by large numbers of jeliasses or rowing galleys.

The reader should know that the kingdoms and lands of Arakan, Pegu and Bengal consist of many flat, low, and very watery lands. The Ganges and the large rivers of Arakan are connected by many tributaries, and this in such a way that one may easily sail from one country to the other. The Arakanese know to make use of this for their war intentions skillfully: with their jeliasses they are sailing down rivers and inner waters, and are looking along the Ganges and in Bengal for any fish that comes to their nets. Wherever possible they disembark, and poach isolated and indefensible villages. The inhabitants are raided in the night and in complete silence.

Any person of who one feels he or she might still serve as a slave is carried away in captivity. These wretched people are then tied up and secured with ropes around their necks and arms in the galleys. They can hardly move, and have to lay under the rowing benches in a miserable way, stretched out on their backs.

These robbers, in the practice of their godless and gruesome profession, must be merciless and certainly as hard as stone. They treat these innocent people in an inhuman way: separating eternally men from their wives, parents from children, and sisters from brothers. Even nursing mothers are torn loose of their tender infants and dragged away. Very old people, ailing persons, crippled ones, and little children are spared by these robbers, not out of pity, but because they are useless in view of their goal, being eager for money.

Anyone can imagine what miserable moaning, weeping and lamentations these wretched people raise. Wretched people who were living in prosperity and freedom the day before, and now, all of a sudden, deprived of everything, tied up and maltreated, poor and naked, and brought to slavery. For a trifling amount they are sold to Christians, Moors, and all sorts of heathen peoples, and thus separated for eternity from each other, and spread all over the earth. Moreover these robbers steal many valuable objects and household goods, and sell this loot on the first and best occasion.

Jeliasses, or rowing galleys, are very long, narrow vessels, and obviously have been constructed in such a way that they can reach a high speed on rivers especially. They do not carry sails, but are equipped with thirty-eight to forty oars. With these, the oarsmen hit the water not simultaneously, but in an orderly and impressive manner rapidly after each other. This way it is just as if one sees a water mill move. Every jelias is usually steered by a Portuguese commander or captain, for whom there is a remarkable little shed on board, in the form of a finely made tent. By the Arakanese kings they are, as we described in the second book already, highly appreciated for their bravery. His majesty takes advantage of these jeliasses by imposing a tribute on them. The wars which are raging between Arakan and Bengal mainly consist of this kind of robberies. Because of the avarice and indolence of the Bengales governors, the Bengalese receive insufficient protection, and thereby it is no surprise that they, as defenseless people, are mortally afraid of these robbers.

Well now, these ten plundering galleys were beginning to act strangely on the river of Pipeli. They made provocative movements by sailing up and down rapidly, and they all hang out their blood flags. Along with this they shouted they wanted to leave, but would return soon, in order to attack and plunder Pipeli by surprise. They prepared all their little pieces or ordnance, muskets, and other rifles, combat-ready. This, clearly visibly, gave rise to great consternation of the Morish governor of Pipeli. Pretty soon one found it desirable to ask the Portuguese living there, and in particular the priest, for advice. After they had consulted him, they decided in a hurry that this priest would write a kind letter to the admiral of the Pottuguese jeliasses. Having done this, however, the real problem came up, and good advice was hard to find, because not one of these Bengalese heroes dared to accept the challenge of delivering this letter. Therefore, after a short deliberation, the letter was given to theDutchmen who now came alongside us with their sloop, after having handed the letter over to the admiral while passing by.

Having read the letter, this person immediately began to stamp his foot and twirl up his moustache, bragging that he would charge at Pipeli after all. Finally, however, this warlord convened his advisors, and after the emotions had calmed down a bit, the robbers decided to reply to the letter as soon as possible. However, they wrote a self-conceited letter full of threats, which gave rise to even greater fright in Pipeli.

The next day, the writing and rubbing went on merrily: envoys, messengers and letters were sent back and forth rapidly. Meanwhile, the crew of the jeliasses were selling some of the captive Bengalese to the Dutchmen: every slave costed twenty rupees, or ten rijksdaalders (4). There were many women and girls amongst them, because it appeared that the men, a bit more agile, had taken to their heels fast. ‘Twas touching to see how these sad persons were sold, and freed from the miserable ties and chains of their mortal enemies, the robbers. Taken on board of our ships, they did not know how to show their joy and happiness, being thankful for the clothes and food they were given.

Dutchmen buying Bengalese slaves from Arakanese robbers at Pipeli

In the end it appeared that all friendly letters from Pipeli to the robbers had been in vain: the robbers were not prepared to make an agreement that would not fully satisfy their conditions. Therefore they came rowing up the river of Pipeli with their ten jeliasses, ready for combat. On the way they made a lot of noise by beating on kettle drums and hung out their blood flags and streamers, whereby the desperate citizens of Pipeli were frightened even more. Nearby the Morish castle they halted, and then took on so terribly as if they were about to exterminate everything by fire and flame.

Immediately they sent one of their men to the Morish governor, to tell him that they had decided to, for the moment, as yet live side by side with the inhabitants of Pipeli in friendship, but only on the condition that their slaves, riches, and loot, would be traded to the needs of the inhabitants against money, fine linen, textiles and other merchandise. If not, they would attack with their jeliasses the unwalled Pipeli with great violence, plunder it and immediately afterwards set it on fire. To this message they demanded a fast and clear reply.

And indeed, what the robbers threatened to do could be implemented with ease, because along the river Pipeli was lying fully open and unwalled, while houses and buildings where big, true, but mainly built out of reed, cow dung, and clay. The houses were scattered everywhere, some buildings consisted of warehouses packed with costly goods. Also, most inhabitants of Pipeli were good soldiers where it came to running away fast. Yet, the population of Pipeli had comprehended for some time already that Arakanese robbers might come here. Now in order to be one step ahead of them they had, on the riverside, a little downstream from Pipeli, put up a fortification by which they hoped, in times of need, to halt the enemy on their route to Pipeli sufficiently. By now, the jeliasses had come close to this ‘excellent’ fortress already, but did not seem to care much about it, although the inhabitants of Pipeli were convinced it was nearly impregnable.

Now the readers are presented with a sample of the art of war of these Bengalese. Ramparts and bastions of this strong ‘castle’ were as much as two feet thick and five feet high, and made of semi-dried clay. The bastions were so frighteningly high that two men could embrace them with stretched arms. From most loop-holes, instead of heavy artillery, chopped-off stems of coconut palm trees were sticking out, which did look scary from a distance. And to give the enemy even more of a fright, they also had collected all the artillery of Pipeli, for one could see two old iron four-pounders standing on one of the bastions. One of those seemed ready to destroy the enemy, for it had been loaded with gunpowder already; the muzzle had been sealed off with a gun barrel wiper made of straw, while the touchhole had been covered with a red stone. Ten cannon balls were lying about, out of which two made of stone and the other six or iron, but all of them much too large. To frighten the enemy even more, an empty hand grenade had been placed there as well. Then there was a pot with at least ten pounds of crude, but useless, gun powder too. Furthermore, of this castle the doors and gates, draw-bridges and ditches, and other works had disappeared, whereby nearly everything was open, and one could get in faster than out in case of need.

Citizens and soldiers of this shaken-up Pipeli now also began to carry on extraordinarily brave and eccentric in this fortification. Their weapons consisted of bows and arrows, shields and swords, as if a fierce mock battle was awaiting them.

After some time the Morish governor of Pipeli, all dressed in white, came riding up like a peace hero. He had a considerable following with him, consisting of a large crowd of black Moors and Bengalese. All of Pipeli appeared to be present. Some were sitting on horses armed with bow and arrow, in their white garments. The brown governor therefore had magnificent company, and, gathering courage, ventured to move along the river to nearby the hostile war fleet.

Having inspected this carefully, he left again, extremely surprised, with his nobles and considerable following for his splendid fortress, which we discussed earlier. Here he entered a hut made of straw with the leading members of his council. They took place on Persian rugs which were lying on the floor, and after mature deliberation one decided to again call in the help of the Portuguese priest of Pipeli.

Once more one requested him to do his utmost for this town and its residents, and go as their envoy on a vessel with a white peace flag to the admiral of the jeliasses. He had to request him to send a capable representative to come and negotiate with the governor and his council peacefully. ‘Lord-uncle’ (5), a fat jolly chap but very smart, was therefore received and treated by the admiral in a very friendly manner, and he managed to bring about that one of the captains of this robbers’ fleet was sent to the governor of Pipeli with full powers. Meanwhile the clever priest remained, ostensibly as a hostage, with the admiral. Quite soon, after some sailing up and down, all differences were settled, and the following was agreed upon:

During the presence of the jeliasses one would not do damage to each other. For a number of days one would allow the galleys to trade freely at Pipeli. Of all goods sold, including gold, silver, gems, and slaves, the Morish governor would receive the tenth penny, to be paid by the buyers, nobody excepted. Residents of Pipeli would have to sell handsome Bengalese commodities on their part, such as fine linen, and silk fabrics. Every evening before sundown the jeliasses had to sail to the Thieves’ Island, which was situated a little downstream, and abstain from robberies and the like over there.

Behold how quickly a war may turn into peace: white flags were hoisted on both sides; gladness and joy amongst the male and female citizens of Pipeli were extraordinary large. Many thousands of people now came out of their houses again, from surrounding areas as well, to have a good look at these terrible plundering galleys for a change. One looked at them with great amazement, because one had heard people speak of them throughout the country. Everyone in Pipeli was glad over the sensible policy of the governor and the agreement made. Now one could also see that the defenseless war heroes had turned into smart salesmen: they were better at the sales- than at the weapons trade. They bought their robbed countrymen back from the Arakanese for a modest price. Some were set free out of pity, others fell into slavery for eternity, according to the buyers’ judgment on their condition and utility. This trade, also the one of all other robbed goods, for money and Bengalese merchandise went on merrily for a couple of days, until at last all goods had been sold. During this period one could speak of a profound mutual friendship. Thereafter the jeliasses left for the Ganges in order to do some more robbing over there, and then return with their loot to Arakan.

This is how time passed over here, while we took in our cargo which had been brought alongside to us from the head office in Houghly, from the Ganges, by small ships with low draught, such as the Lindenburg, Wakende Boei and ‘t Nachtglas. The cargo consisted of saltpetre and silk. Our comrade, the fluytship Amstelland, left for the anchorage of Kinnica (6) in order to take in rice over there. This was four miles south of Jaggernate (7), where they were building a new warehouse. …….. (8)

Footnotes

2 In those days, the Netherlands were the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands, also called the Republic of the Seven Provinces (1588 – 1795).

3 Now: Jakarta

4 One rijksdaalder was two-and-a-half Dutch guilders; one guilder was 100 cents

5 Translation of Heeroom, a colloquial Dutch word to denote priests in an affectionate way

6 Was probably situated at Chilika

7 The Black Pagoda, d.i. Puri

8 Follows one more page, with information on the return to Batavia